Biography

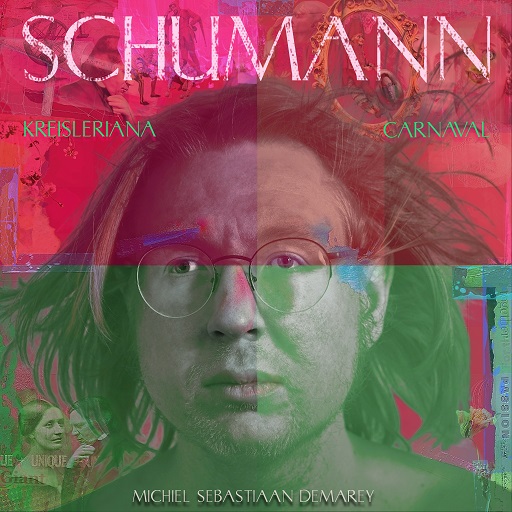

Michiel Sebastiaan Demarey

Find this album here

My name is Michiel Demarey, a 38-year-old pianist from Belgium.

I started playing music when I was five. I had a little Casiotone keyboard and would pick out melodies I heard from the church bells outside. The first one I figured out was *Ode an die Freude.* From the beginning, music made sense to me—at least by ear.

When I was six I started doing everything by ear. Bach, Chopin, Liszt, Debussy. I listened, then played.

One day, the phone rang. This man told me he believed I was a musical genius—his words—but that solfège was essential for production. He invited me to join his music school for an intensive course to catch up on the basics.

I had a piano teacher who assumed I’d be playing pop music. But when I told her I wanted to study *Pictures at an Exhibition* and Rachmaninoff’s *Études-Tableaux*, she was surprised in the best way. She gave me a phone number to call. In the background, someone was playing *Rachmaninoff Op. 39 No. 6*—the very piece I had prepared. My stomach dropped. But I sat down at the Bechstein and played.

The man listening was Vitaly Samoshko, First Prize winner of the Queen Elisabeth Competition. He invited me into his piano class.

At the entrance exam, I was so nervous I drank liquor just to make it on stage. I ended up improvising Bach’s Prelude in G major—but in G-sharp major. My Rachmaninoff sounded like it was underwater. Still, Samoshko believed in me. He accepted me anyway.

Samoshko offered it to me as an alternative to Schumann’s Toccata, which I couldn’t play due to hand size. That night, I had a dream to record Kreisleriana.

So I did. Since then, I’ve continued recording. My version of *Carnaval* includes even the silent Sphinxes. They hold meaning for me—masonic, erotic, sacred. In the “Chopin” section, I improvised.

The great musicologist Charles Timbrell—editor of the *Kreisleriana* score—heard my recording. He included it in his top three interpretations of all time, alongside Horowitz and Natan Brand. That meant more than I can say.

Warmly,

Michiel